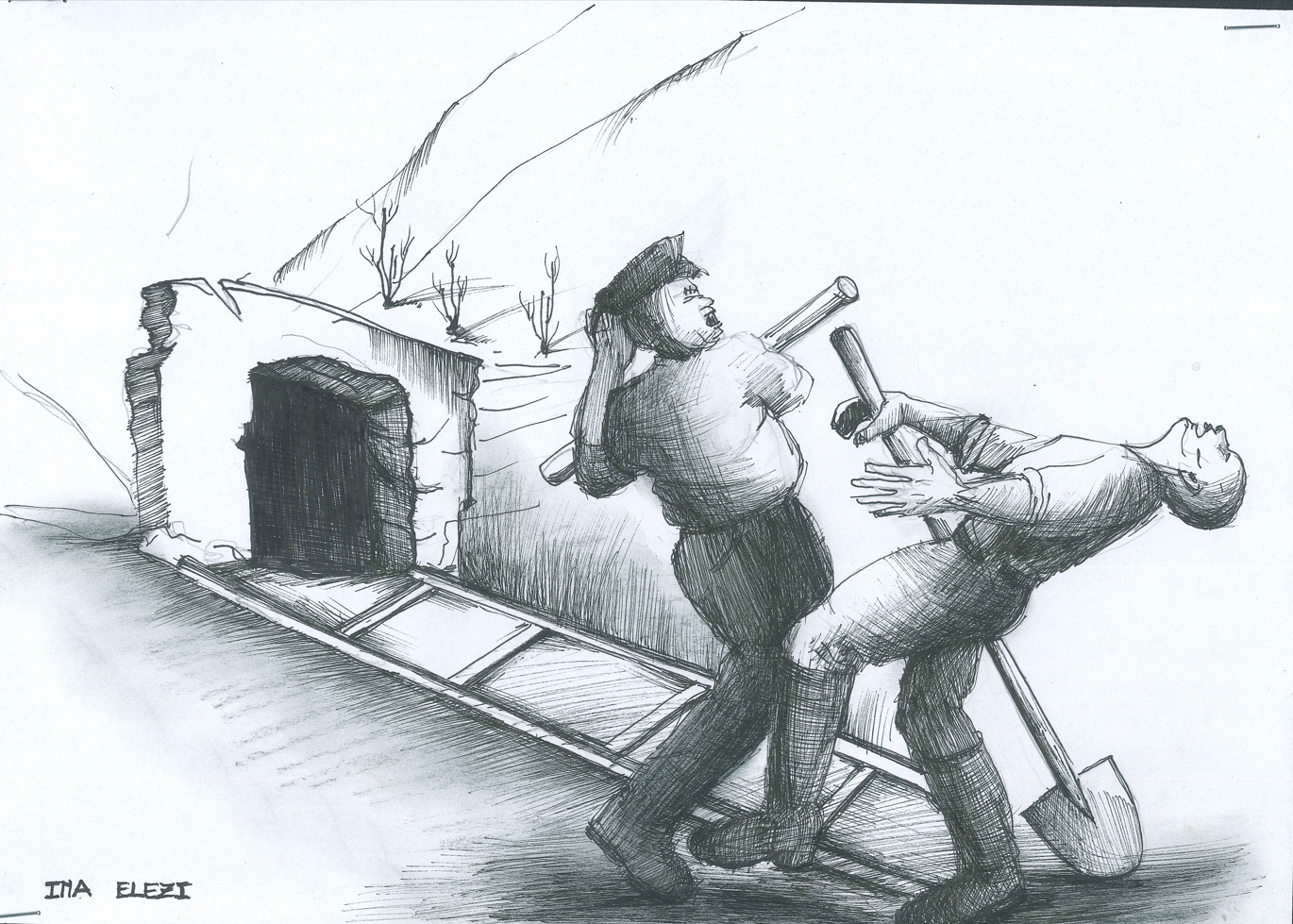

Meeting the rates was often impossible. Few prisoners could physically handle that titanic load at work. In many cases during the cave-ins in the tunnel, there was not enough mineral to fill seven wagons. But prison command never accepted any justification for not meeting the rate. The most common expression of officers in Spaç was “Either your plan (target) or your soul”, which implied that death awaited all those who didn’t give the regime whatever was required at all costs.

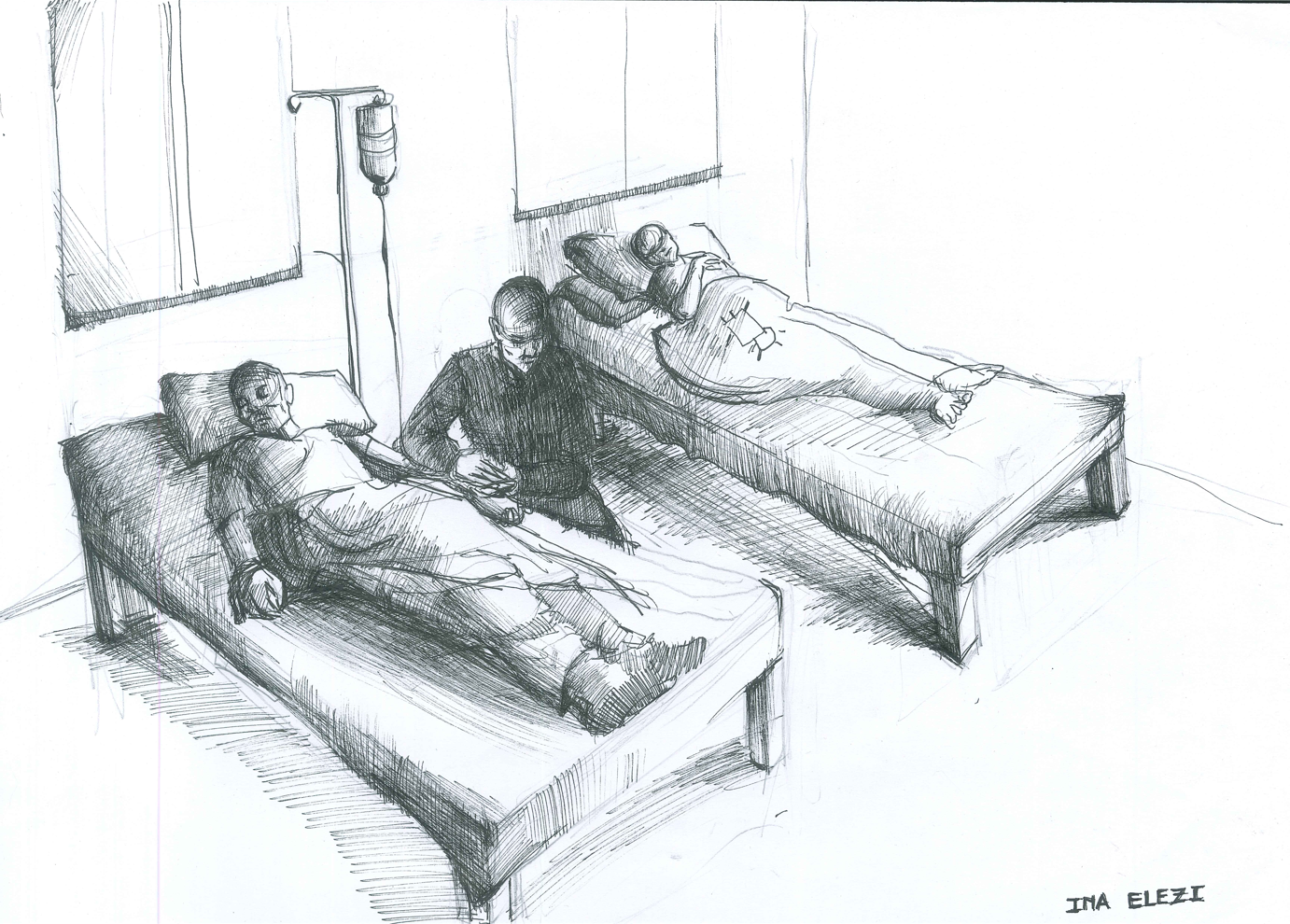

Spaç Prison Camp had an infirmary with eight beds. This infirmary was designed to meet all of the camp’s health needs. But referring to some periods of high intake of patients (wounded in accidents, with a cold, poisoning from food or underground gases in tunnels, chronic diseases or many other health concerns), the infirmary didn’t meet even the most minimal needs of prisoners.

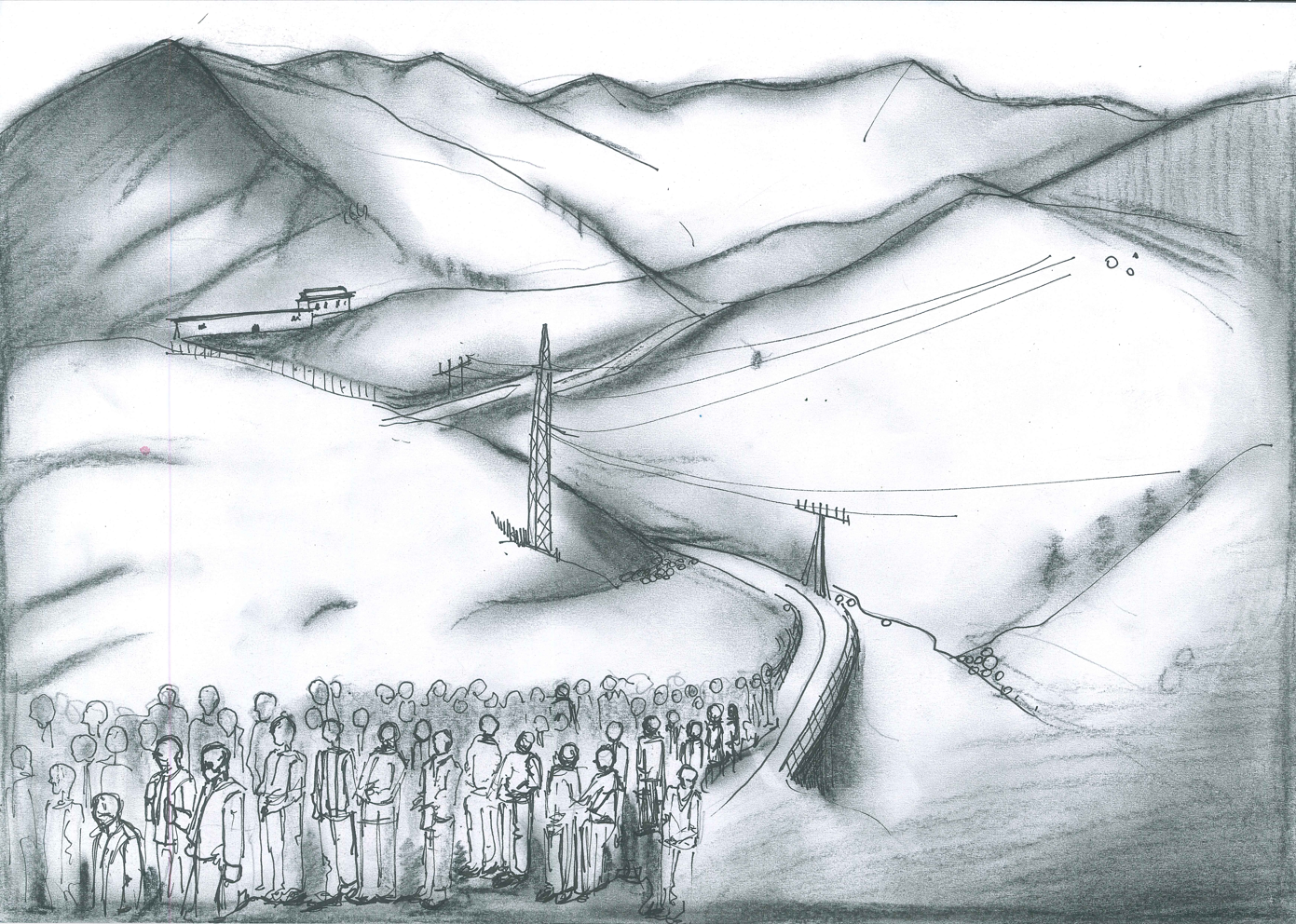

After ending eight hours of forced labor, prisoners delivered their work tools and got ready to start their downwards walk to the camp entrance. At the camp entrance, all prisoners went through a daily check by guards as the latter feared that prisoners could be holding tools they took out of the tunnels to return in hiding to the camp. Another check was done if all prisoners were present or not, as it often happened during shift hours that prisoners who entered the tunnel would be able to find hidden exits and leave the camp’s enclosure and escape. Around two hours after finishing their shift and checks, prisoners went to the cafeteria to eat lunch and after exactly one hour go through roll call. Later, the command had free time to fill mainly through obligatory readings of the regime’s party propaganda. Afterwards there was dinner and at around nine in the evening, sleeping time started for the first shift.

In the pyrite area the daily rate for each working group was seven wagons. As such, the two carters of the group had to fill seven wagons of mineral. According to former prisoner Shkëlqim Abazi’s testimony, a wagon would take around 200 shovels of pyrite to fill. A shovelful of pyrite weighed from 18 to 25 kg. According to an average number, one wagon had around 3,600 kg of pyrite. This estimate would mean that the two carters had to fill seven wagons, or 25,200 kg of mineral per shift, or 12,600 kg of mineral each. Imagine the daily routine for this enslaving work where one man had to load 12,600 kg of mineral every day!

Beyond the grueling process of this mineral’s extraction, pyrite tunnels were far more dangerous than copper ones. The terrain was highly unstable due to the mineral’s acid sand-like composition, therefore collapses in pyrite tunnels were quite often. Furthermore, the acid environment made work all the harder. Acid drops that dripped ceaselessly in the tunnel not only eroded and burnt the prisoner’s unprotected skin; they also eroded and destroyed the rails on which prisoners had to push their wagons. This added on to the exhausting work: as the wagons had to be pushed for around one kilometer and the same distance back.

Those who didn’t meet the target were often tied to a column at the tunnels’ exit and left there tied all night or day until the end of the shift. The torture was severely more excruciating during extreme frosts.