Based on rare images that managed to film the area after the fall of the dictatorship at the beginning of the ‘90s, Spaç Camp looked like this. The last political prisoners left the camp in June 1990.

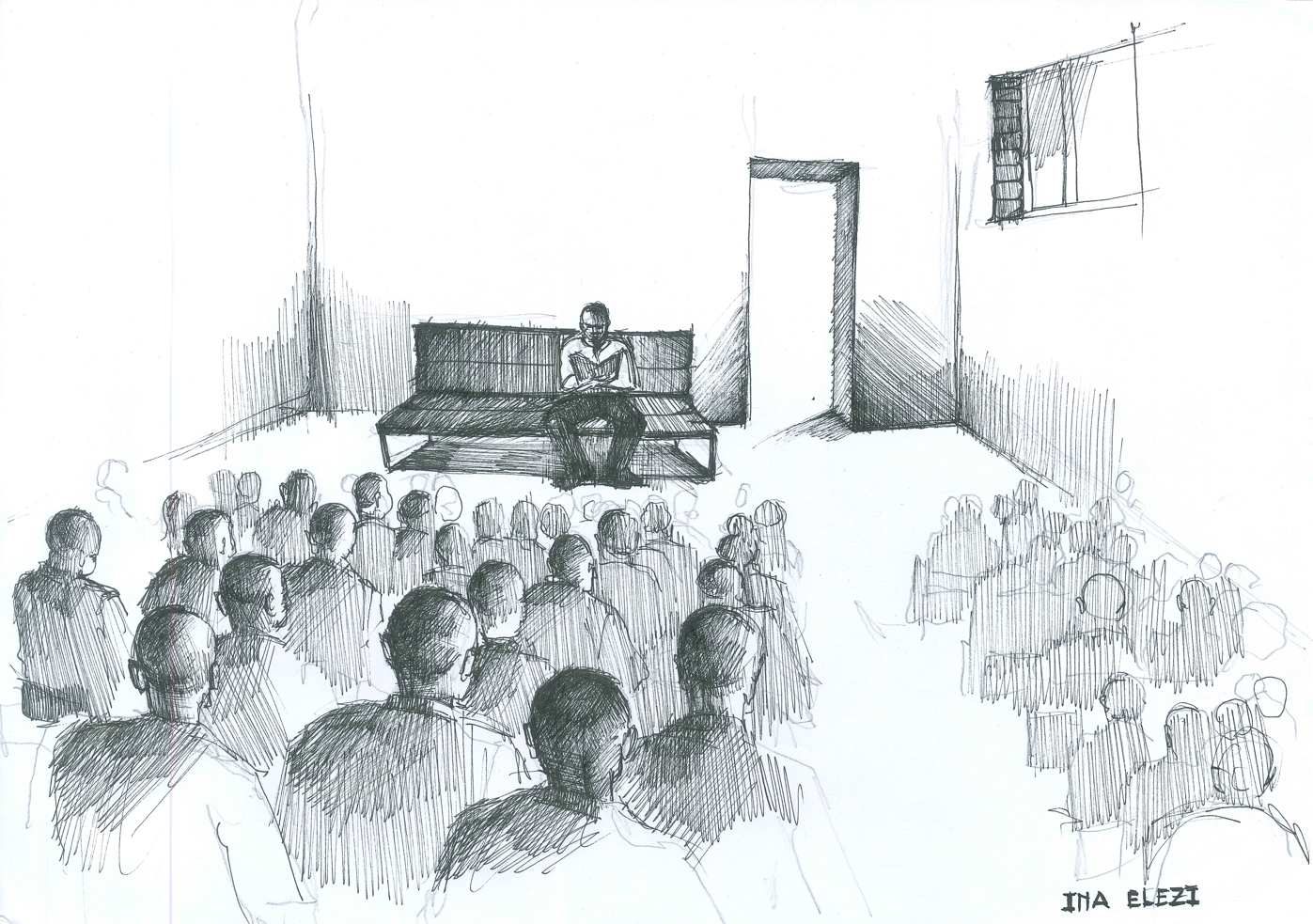

Afternoon at the camp for first-shift prisoners continued after roll call with what was called ideological education. In the camp library, the literature and press of the Labor Party of Albania was read. We learn from many testimonies that this process started from 05:10 pm to 7:30 pm. For the prisoners of conscience, this was another form of psychological violence.

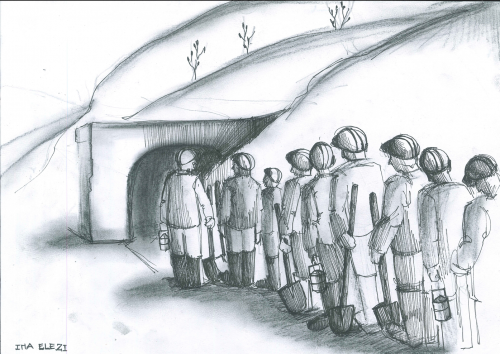

The tunnels’ entrance had small barracks with boards and sheet metal, which stored the prisoner’s working tools such as: axes, pickaxes, shovels, hammer drills, mining drills (hexagonal section rods of different lengths from 50 to 150 cm placed in the hammer and drilling holes where the explosive device would be put).Before entering the mine, the prisoners would be divided in groups of three, where one was a miner and two were carters.After taking their work tools, they would enter the tunnel and go to the exploded area to start work.

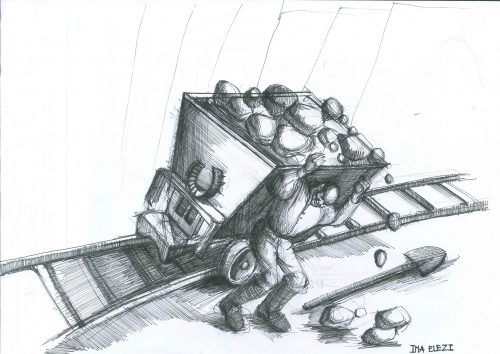

The tunnels’ amortization was one of the largest impediments of the prisoners’ work process and often in their testimonies they recalled that the greatest difficulty was raising a wagon when it derailed and fell. The prisoner was forced to raise the wagon on his own using his shoulders and upon restoring it on the rails, he refilled it with the fallen mineral.

At Spaç Camp there was a store, a 4x4m building near the smith’s. Prisoners, referring to the seller’s name, called it Ndue’s store. The store was state-owned and the seller was a free man who came to the camp every day. In ShkëlqimAbazi’s testimony, it is indicated that “…in Spaç’s Revolt, political prisoners undertook not to touch the store, even if people would be starving. They guarded it to make sure nobody attacked it. So, it wasn’t touched.”

The store often sold food products like sugar, flour, rice, oil. There were also some stationeries, like pencils, pens, notebooks, envelopes, etc.

But how did prisoners buy when physical money was prohibited in camp? ShkëlqimAbazi explains in his testimony: “We had no money in the physical sense. We had imaginary money if we can call it that. Our money existed in the accountant’s office, who marked the money prisoners earned by work or those their families brought. Until 1972, the law in force dictated that no matter how much you worked, the most you can earn is 18 leks. The accountant noted the income collected for each prisoner. Before going to the store you placed the order at the accountant: e.g., he would order 1 kg of sugar, oil, pasta, for which he would get a coupon. He’d open the records and check: Shkëlqim has, let’s say, 1,000 leks. Deduct 500 leks, and 500 leks remain. If the balance didn’t match, you didn’t get a coupon. This was the money we used: the coupon.”

Temperature in pyrite tunnels changed extremely compared to temperature out of tunnels, where prisoners got out to empty their wagons. Inside, temperatures varied from 50 to 60 degrees Celsius, whereas winter temperatures hit -20 degrees Celsius outside. In winter, prisoners worked naked inside the tunnels, whereas outside they wore fur coats they stored at the entrance to protect themselves somewhat from the extreme change of temperature. This was the cause that the predominant disease of the camp was the cold. It accompanied prisoners for as long as they were forced to live in that hell.