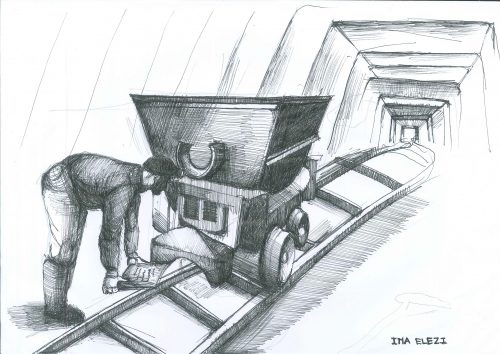

This is a sketch of the clothes warehouse, where prisoners would keep their work clothes and dress to get ready to go to the mine.The warehouse had cotton fur costumes, rubber boots, puttees, miner’s caps, etc.

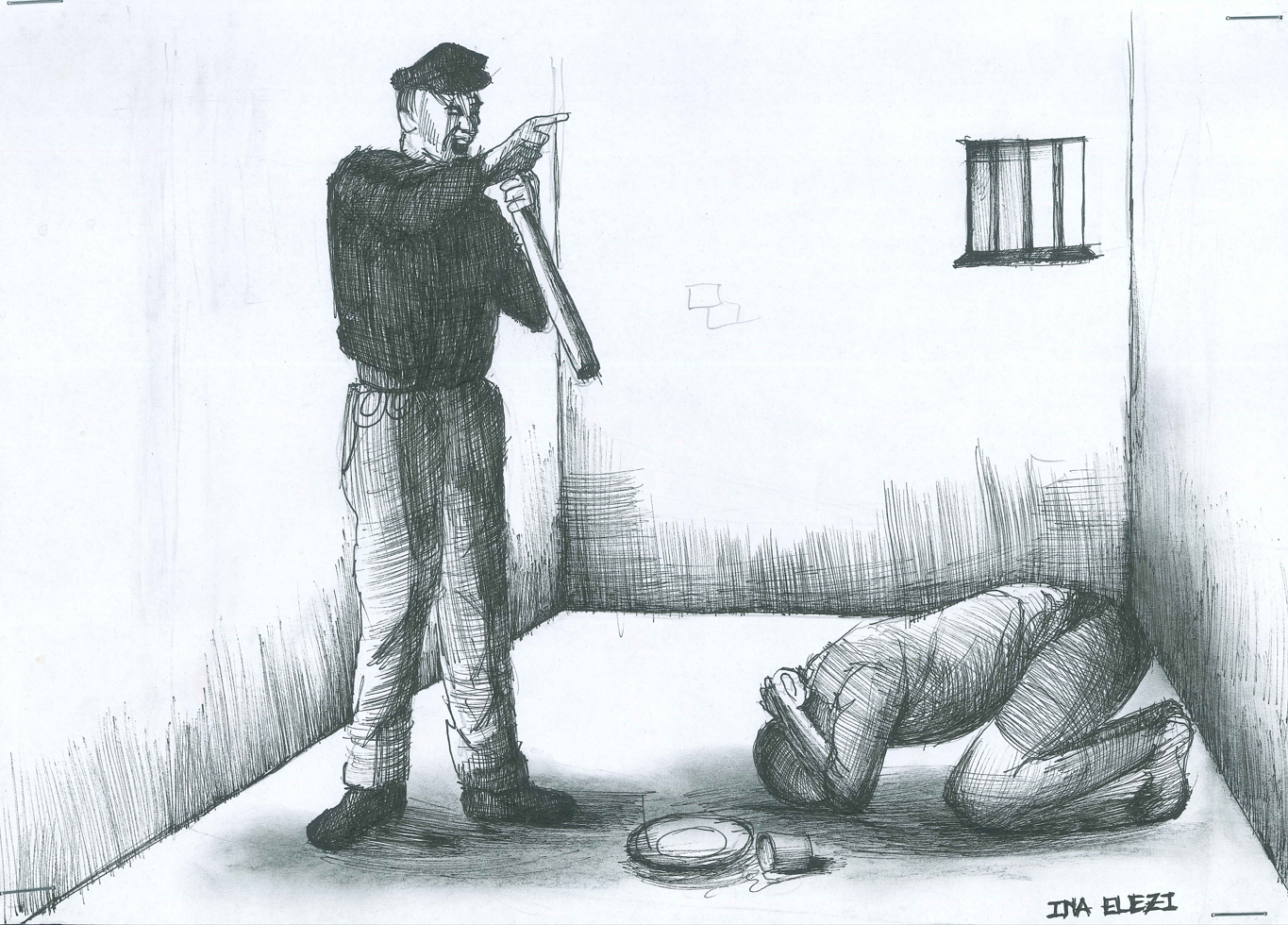

Upon their return, rebel prisoners who refused to work were put in cells and left in isolation up to 30 days. In official records, we discover that only in the first half of 1980, 118 convicts had been put to the cell.

In the sleeping areas, prisoners secretly distributed Albanian translated works, which were not allowed by camp command. They were copied and re-copied and prisoners circulated them to be read by everyone. Convicted writers and poets also circulated their poems. Often police officers in the camp did detailed checks and if they were caught, these were cause for re-conviction. That was why manuscripts were often hidden in the mine, in different places like airing pipes or special spots created by prisoners themselves in the tunnels’ wooden reinforcement structure.

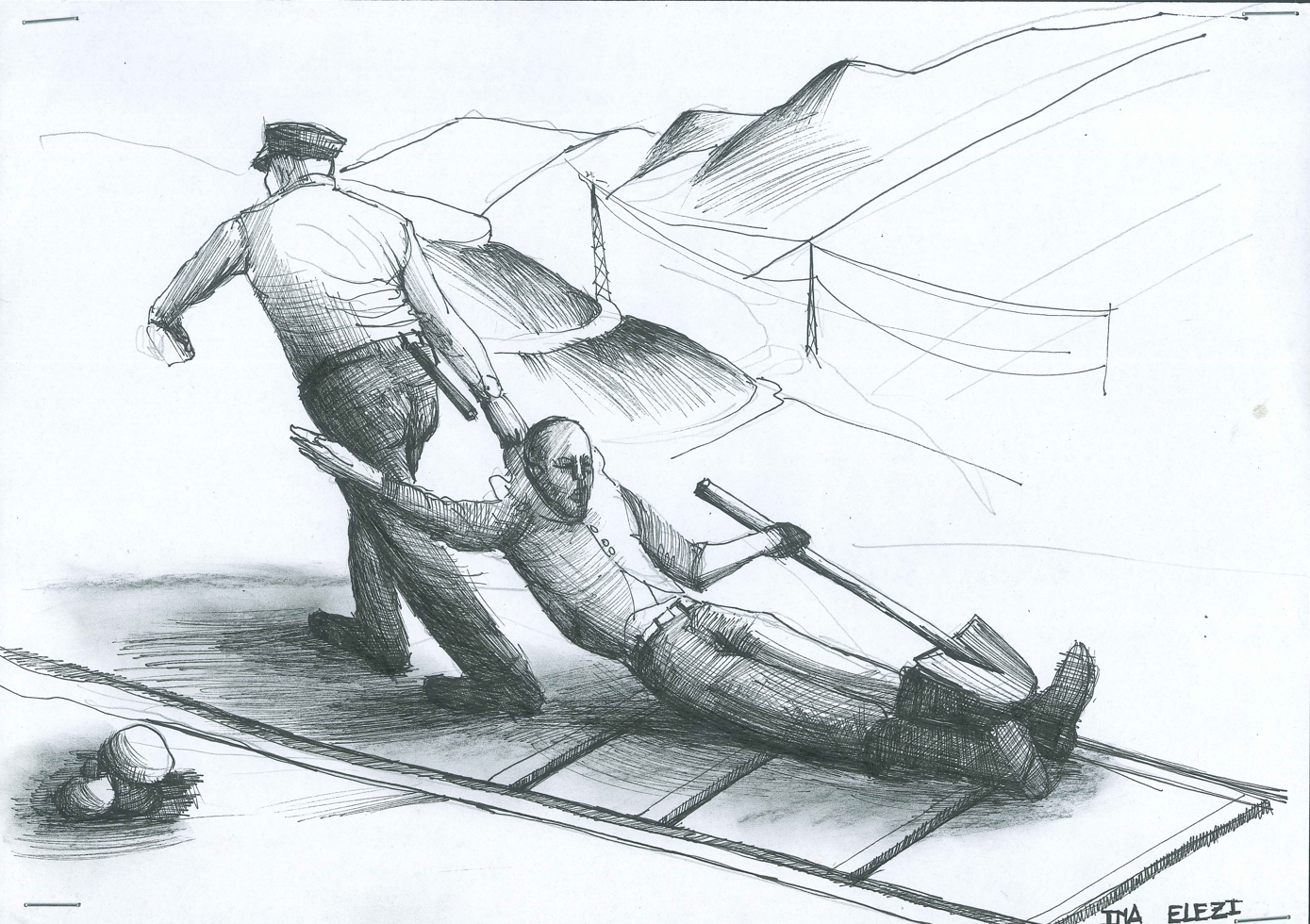

Anyone who didn’t meet his target was forced back to the tunnel with the other shift and held there until the end of that shift with no food or rest at any given moment until they met their daily target. Police officers inflicted extraordinary violence to those prisoners who refused to enter the tunnel.

Afternoon at the camp for first-shift prisoners continued after roll call with what was called ideological education. In the camp library, the literature and press of the Labor Party of Albania was read. We learn from many testimonies that this process started from 05:10 pm to 7:30 pm. For the prisoners of conscience, this was another form of psychological violence.

In the first years of the camp’s operation, in the years 1968-1971, there were four sleeping areas in Spaç, which were one-story barracks made of mixed concrete.Later in the camp, three-story sleeping areas were built, where every room housed 35 to 50 prisoners.Their number depended on the intake of arrests and political convictions pronounced by the regime. The sleeping areas’ routine was almost the same.That’s where prisoners passed most of their time after eight hours of exhausting work in Spaç’s mines. Sleeping and waking hours were closely related to the three-shift timetable applied for work in the mine.

There was one room where the prisoners slept, particularly after going from one-story barracks to three-story ones, as the sketch indicates, which was full of these bunk beds connected to one another mainly in a U shape and equipped with wooden stairs to climb to the upper bed.Prisoners shared their common space with no separation between mattresses and when the number of prisoners increased, everybody had even less space to give room to the newcomers.