Upon their return, rebel prisoners who refused to work were put in cells and left in isolation up to 30 days. In official records, we discover that only in the first half of 1980, 118 convicts had been put to the cell.

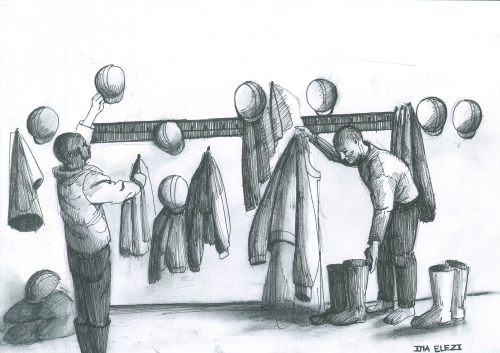

Prisoners in Spaç were also provided with prison clothing, which was used both during work and rest in the camp.The provision for each prisoner included:two cotton twill costumes a year, a brown fur coat (stuffed with cotton waste) once every three years, two pairs of long underpants and two stiff poplin shirts, which, as ex-prisoner Shkëlqim Abazi testifies, “that fabric rubbed on the skin like sandpaper”, two pairs of puttees (square pieces, the same material as shirts, with which they wrapped their feet before putting on their boots, when they went to the mine), a pair of rubber moccasins and a cloth hat like the puttees’ fabric.At the beginning of the ‘70s, a cotton twill fur costume was added, stuffed with cotton waste and sewn with seams to hold the cotton inside.This product was designed to better handle the cold in the mine, but it was very heavy and uncomfortable for the mine’s conditions, adding to the prisoners another form of suffering, as it would absorb the humidity during the eight hours in the mine, increasing manifold the miners’ weight by the time they exited.During winter they would not dry until the next day and were thus often a source of disease for prisoners.Prisoners were also provided with a cotton twill jacket thinly coated with resin that served as mackintosh.The uniform also had two pairs of gloves and wool socks and two pairs of rubber boots and a carton cap.The work clothes were held at the clothes warehouse in the camp.

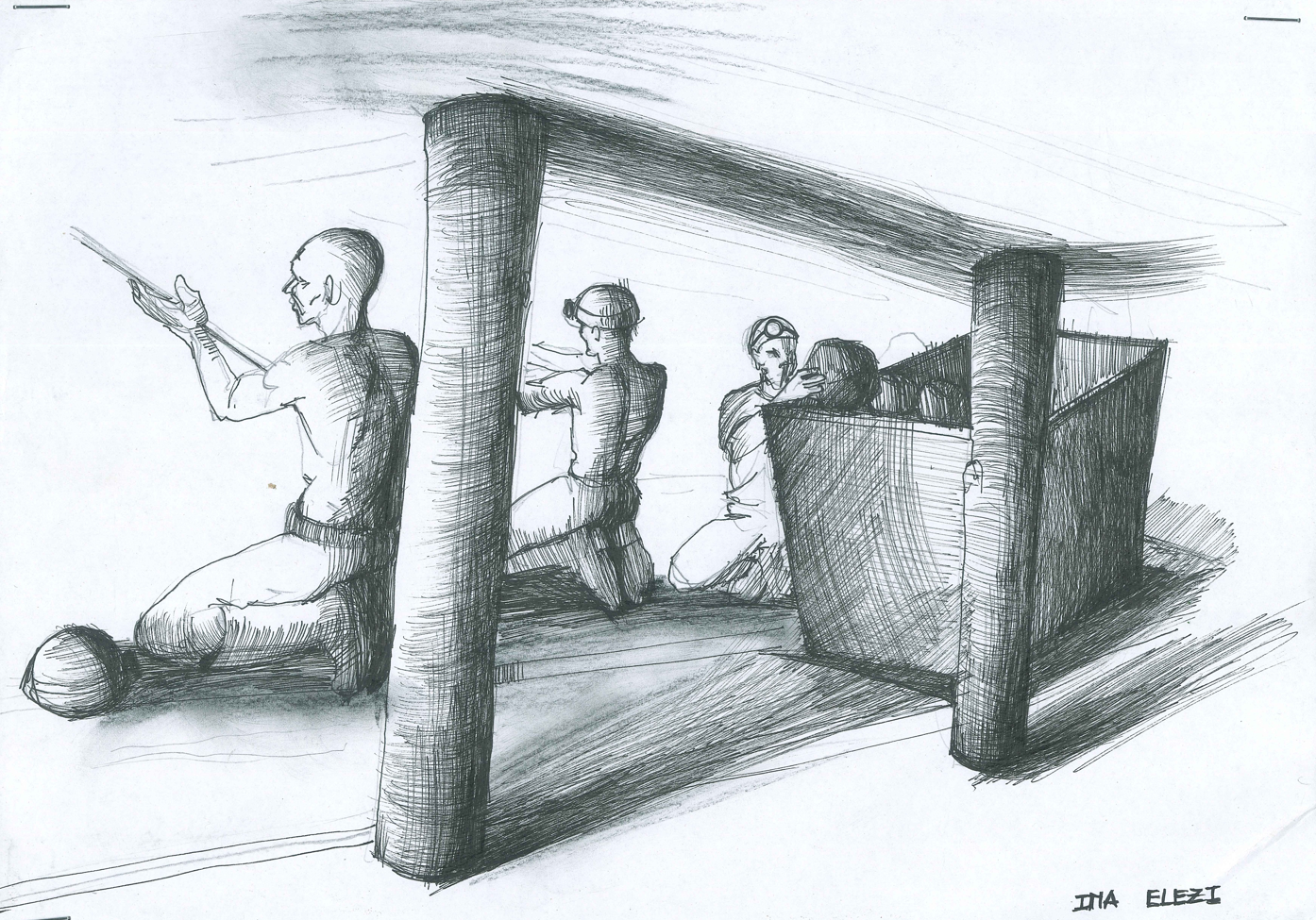

Whereas the two carters continued the reinforcement process, the miner hammered holes to put the explosive in and then detonate it after exiting the mine. All of the rocky mass exploded by the dynamite would be the new work front for the successive shift. The second shift would follow the same routine as the first and then leave the area for the third.

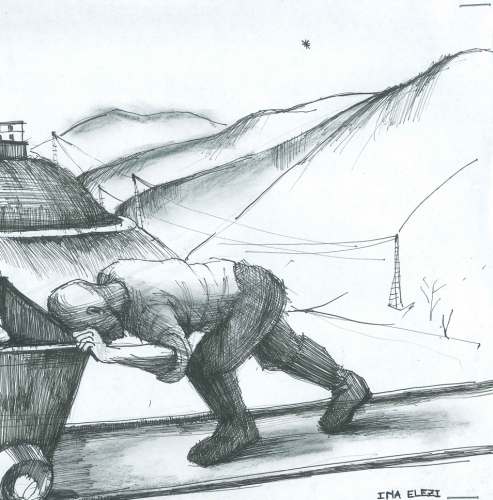

In the pyrite area the daily rate for each working group was seven wagons. As such, the two carters of the group had to fill seven wagons of mineral. According to former prisoner Shkëlqim Abazi’s testimony, a wagon would take around 200 shovels of pyrite to fill. A shovelful of pyrite weighed from 18 to 25 kg. According to an average number, one wagon had around 3,600 kg of pyrite. This estimate would mean that the two carters had to fill seven wagons, or 25,200 kg of mineral per shift, or 12,600 kg of mineral each. Imagine the daily routine for this enslaving work where one man had to load 12,600 kg of mineral every day!

Beyond the grueling process of this mineral’s extraction, pyrite tunnels were far more dangerous than copper ones. The terrain was highly unstable due to the mineral’s acid sand-like composition, therefore collapses in pyrite tunnels were quite often. Furthermore, the acid environment made work all the harder. Acid drops that dripped ceaselessly in the tunnel not only eroded and burnt the prisoner’s unprotected skin; they also eroded and destroyed the rails on which prisoners had to push their wagons. This added on to the exhausting work: as the wagons had to be pushed for around one kilometer and the same distance back.

In rare cases when there was little time before the evening, prisoners spent their time with conversations, simple games, hidden readings, and foreign language learning in secret. Foreign language learning was prohibited by the camp’s command. This accusation was frequently collected by depositions of spies who had infiltrated in the sleeping rooms and were often used as evidence to re-convict prisoners.

Afternoon at the camp for first-shift prisoners continued after roll call with what was called ideological education. In the camp library, the literature and press of the Labor Party of Albania was read. We learn from many testimonies that this process started from 05:10 pm to 7:30 pm. For the prisoners of conscience, this was another form of psychological violence.